Introduction to Special Relativity

Tuesday, January 18, 2022

Classical Relativity

What is relativity?

In general, the concept of relativity allows observers in different frames of reference to compare observations of phenomena.

Inertial frames of reference are those that do not involve any rotation or acceleration, where all of Newton's laws apply. Examples of an inertial frame of reference would be floating in a non-rotating rocket in interstellar space, away from any meaningful effects of gravity. The surface of Earth is sometimes accepted as close enough to inertial for some observations, but observers are still subject to Earth's gravitational force and rotation.

A transformation describes how to change observations from one frame of reference into another. Transformations are often expressed as a system of equations, comparing two observers' (often denoted and ) perceived location in spacetime, .

Galilean transformations

In classical physics, a set of transformations known as Galilean transformations are used. For an observer moving at velocity in the positive direction with respect to observer , the following equations describe the classical relativity:

Note: the last equation, , means that in Galilean transformations time is the same for all observers.

Taking the derivative of each equation with respect to time (this works because time is the same for all observers), we find the Galilean velocity transformations as such:

Finally, the Galilean acceleration transformations are as follows:

The Michelson-Morley Experiment

Physicists postulated about a medium called ether, which light waves propagated through, to explain relativistic effects to do with light.

To test their hypothesis, Michelson and Morley used monochromatic light split by a half-silvered mirror. This would then reflect half of the light and let the other half pass through. The light beams would then be reflected by mirrors, and recombined in the center before being shone on an observing plate.

Any phase difference in the light would result in interference, meaning there would be bands of light. Michelson and Morley suspected this phase difference would result from two factors:

- The slight difference in distances between the mirrors on their experimental setup

- The effects of the ether wind on the light waves (the idea was that light would move faster one way because of a backwind and faster another way because of a headwind)

To cancel the effects of the first factor, they rotated their apparatus 90 degrees to change the setup's movement through the ether (all the cross-stream ether wind would become upstream/downstream and vice versa). After careful observation, however, they saw no noticeable difference in the fringe pattern produced by the light, meaning their theory of such a medium was unsupported.

Einstein's Postulates

Einstein's special theory of relativity attempts to accurately describe the motion of particles (including light) moving at high velocities, where classical relativity falls short.

The theory is based on two postulates:

- The principle of relativity: the laws of physics are the same in all inertial frames of reference

- The principle of the constancy of the speed of light: the speed of light in free space has the same value, , to all observers in inertial frames of reference

These postulates mean there can be no physical laws that are valid in one inertial frame of reference and invalid in any other inertial frame of reference. Additionally, this means there is no "preferred frame of reference" for observations in the universe.

Due to the constancy of the speed of light, Galilean transformations do not suffice. Instead, relativistic transformations are used.

The Special Theory of Relativity

Time dilation

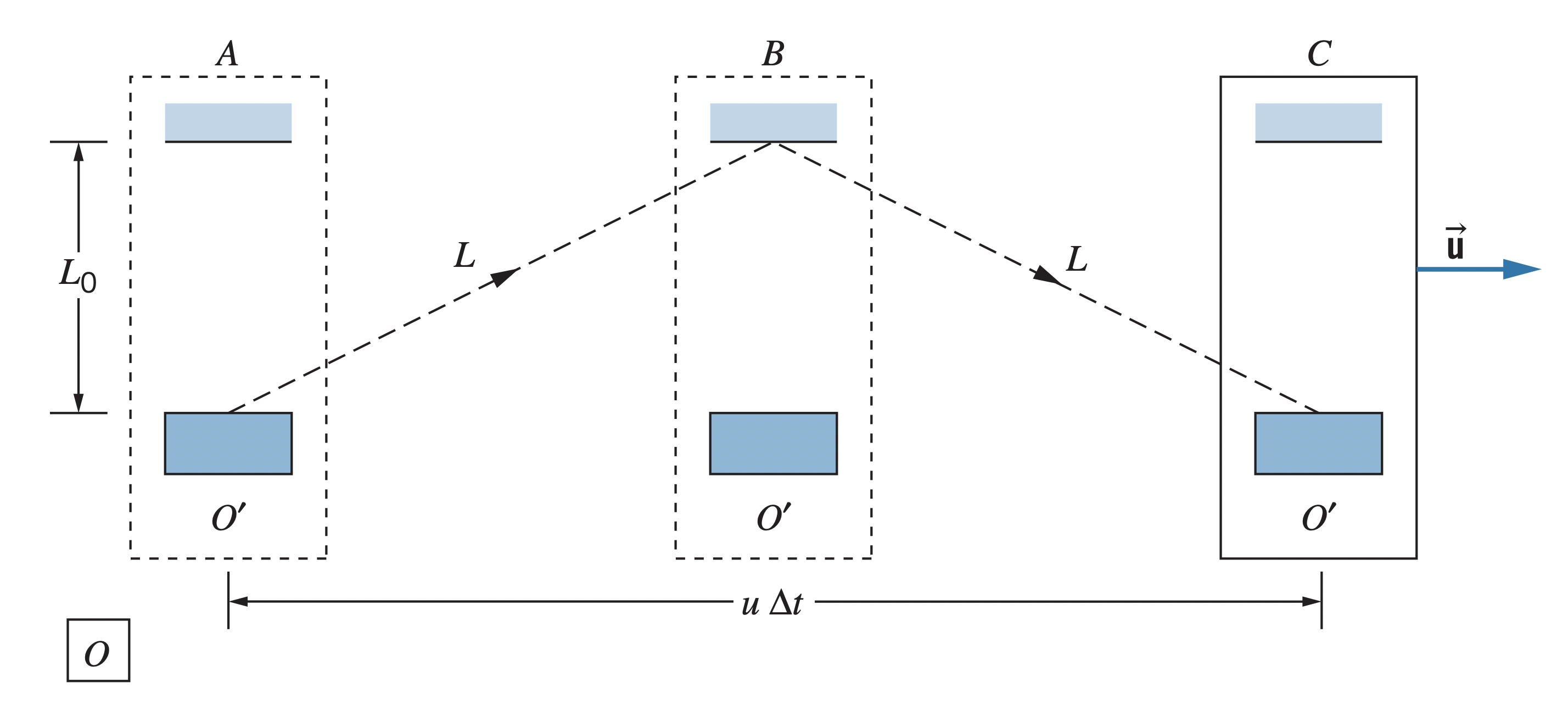

Since light moves at the same speed for all inertial observers, a stationary observer relative to a moving one will perceive time passing slower for the moving observer. In the image below, observer sees the light moving a distance (therefore taking ), whereas observer sees the light traveling a distance (therefore taking ). Since , .

This effect, called time dilation is described by the following equation, where is the time measured by the observer and is the time measured by observer :

, called the proper time, is the time as measured such that the location of the object does not change with respect to what the observer are measuring. For example, for the image above, the proper time would be the time that observer measures, since they do not move with respect to the clock.

Length contraction

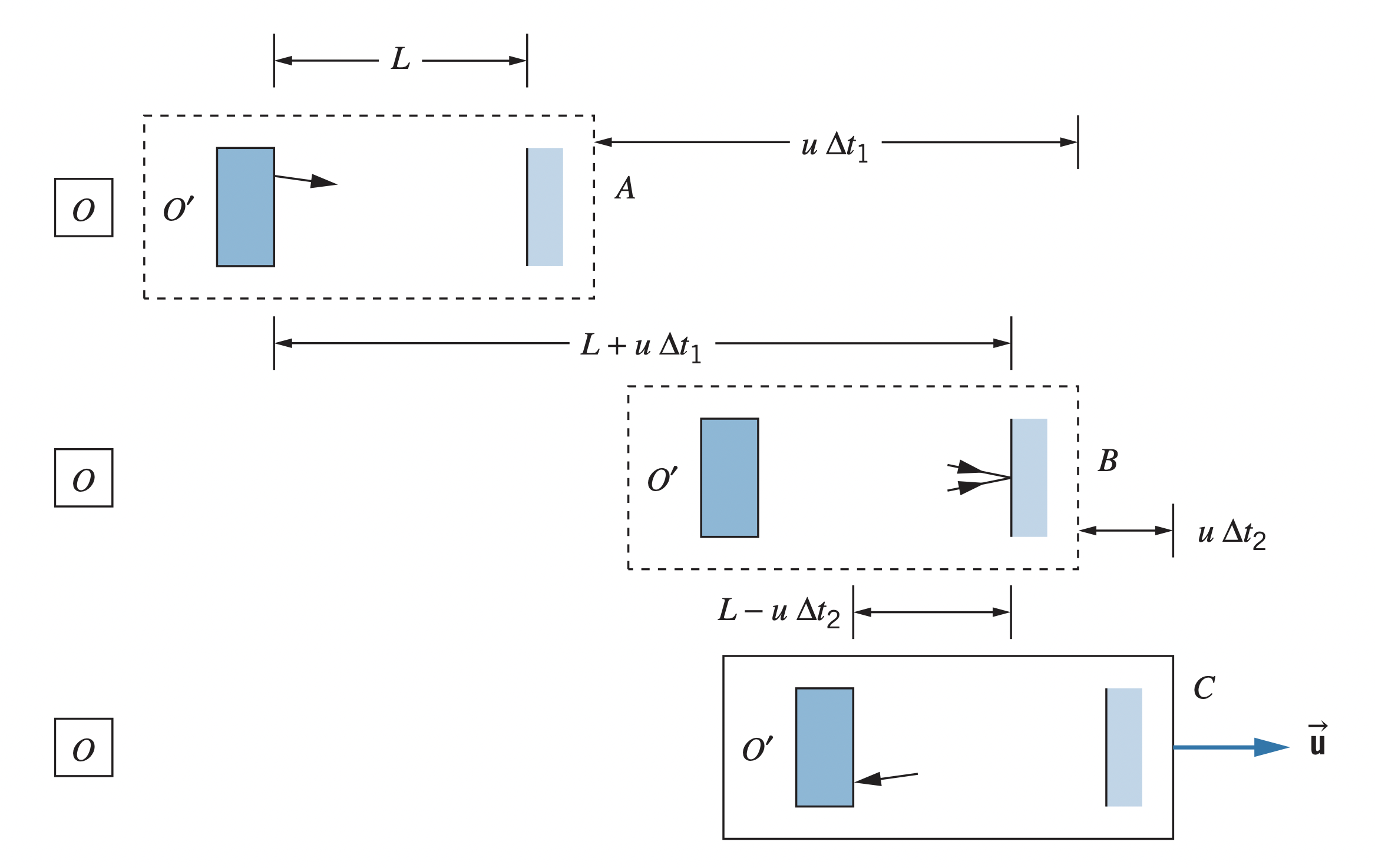

Similarly, for an object moving away from an observer, light needs to travel a shorter distance than it would need to if the object were stationary (see image below).

This results in the effect known as length contraction, which is described by the equation below:

Stationary observers always measure objects moving to be shorter than they would be if they were stationary. The proper length, , is the length measured at the same instant in time, by the observer not moving with respect to the object.

Simultaneity

Due to the effects of length contraction and time dilation, events that appear to be simultaneous to one observer are not necessarily simultaneous to another.

Simultaneity is relative

Relativistic velocity addition

Due to the effects of length contraction and time dilation, velocities do not simply add together in special relativity. If they did, objects moving very fast relative to other objects moving very fast could move faster than the speed of light. To correct for this, the following equation is used:

Note: when either or equals the speed of light, also equals the speed of light, regardless of the other velocity.

Relativistic doppler shift

Because of a lack of reference medium for light, classical doppler shift does not work when analyzing light. Instead, the relativistic doppler shift equation is used: